Case Study: First Image of a Black Hole

Black Hole M87 (Image Credits: Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration)

Imaging the M87 Black Hole is like trying to see something that is by definition impossible to see.

A telescope the size of the earth

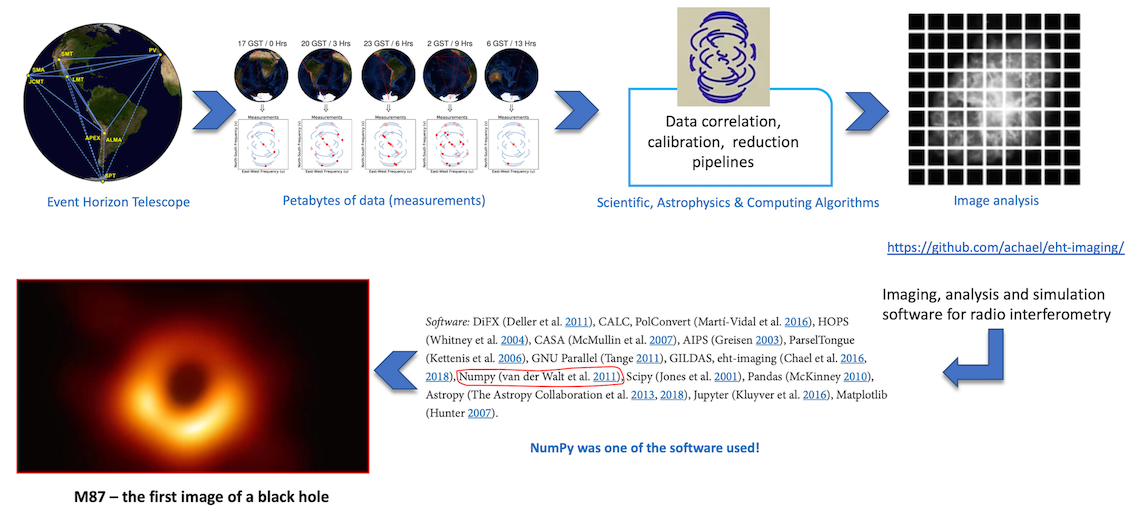

The Event Horizon telescope (EHT) is an array of eight ground-based radio telescopes forming a computational telescope the size of the earth, studing the universe with unprecedented sensitivity and resolution. The huge virtual telescope, which uses a technique called very-long-baseline interferometry (VLBI), has an angular resolution of 20 micro-arcseconds — enough to read a newspaper in New York from a sidewalk café in Paris!

Key Goals and Results

-

A New View of the Universe: The groundwork for the EHT’s groundbreaking image had been laid 100 years earlier when Sir Arthur Eddington yielded the first observational support of Einstein’s theory of general relativity.

-

The Black Hole: EHT was trained on a supermassive black hole approximately 55 million light-years from Earth, lying at the center of the galaxy Messier 87 (M87) in the Virgo galaxy cluster. Its mass is 6.5 billion times the Sun’s. It had been studied for over 100 years, but never before had a black hole been visually observed.

-

Comparing Observations to Theory: From Einstein’s general theory of relativity, scientists expected to find a shadow-like region caused by gravitational bending and capture of light. Scientists could use it to measure the black hole’s enormous mass.

The Challenges

-

Computational scale

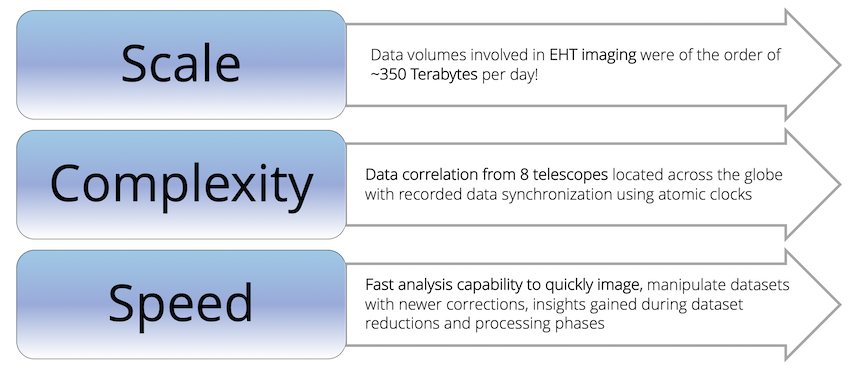

EHT poses massive data-processing challenges, including rapid atmospheric phase fluctuations, large recording bandwidth, and telescopes that are widely dissimilar and geographically dispersed.

-

Too much information

Each day EHT generates over 350 terabytes of observations, stored on helium-filled hard drives. Reducing the volume and complexity of this much data is enormously difficult.

-

Into the unknown

When the goal is to see something never before seen, how can scientists be confident the image is correct?

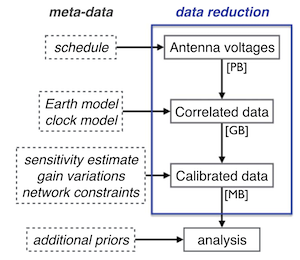

EHT Data Processing Pipeline (Diagram Credits: The Astrophysical Journal, Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration)

NumPy’s Role

What if there’s a problem with the data? Or perhaps an algorithm relies too heavily on a particular assumption. Will the image change drastically if a single parameter is changed?

The EHT collaboration met these challenges by having independent teams evaluate the data, using both established and cutting-edge image reconstruction techniques. When results proved consistent, they were combined to yield the first-of-a-kind image of the black hole.

Their work illustrates the role the scientific Python ecosystem plays in advancing science through collaborative data analysis.

The role of NumPy in Black Hole imaging

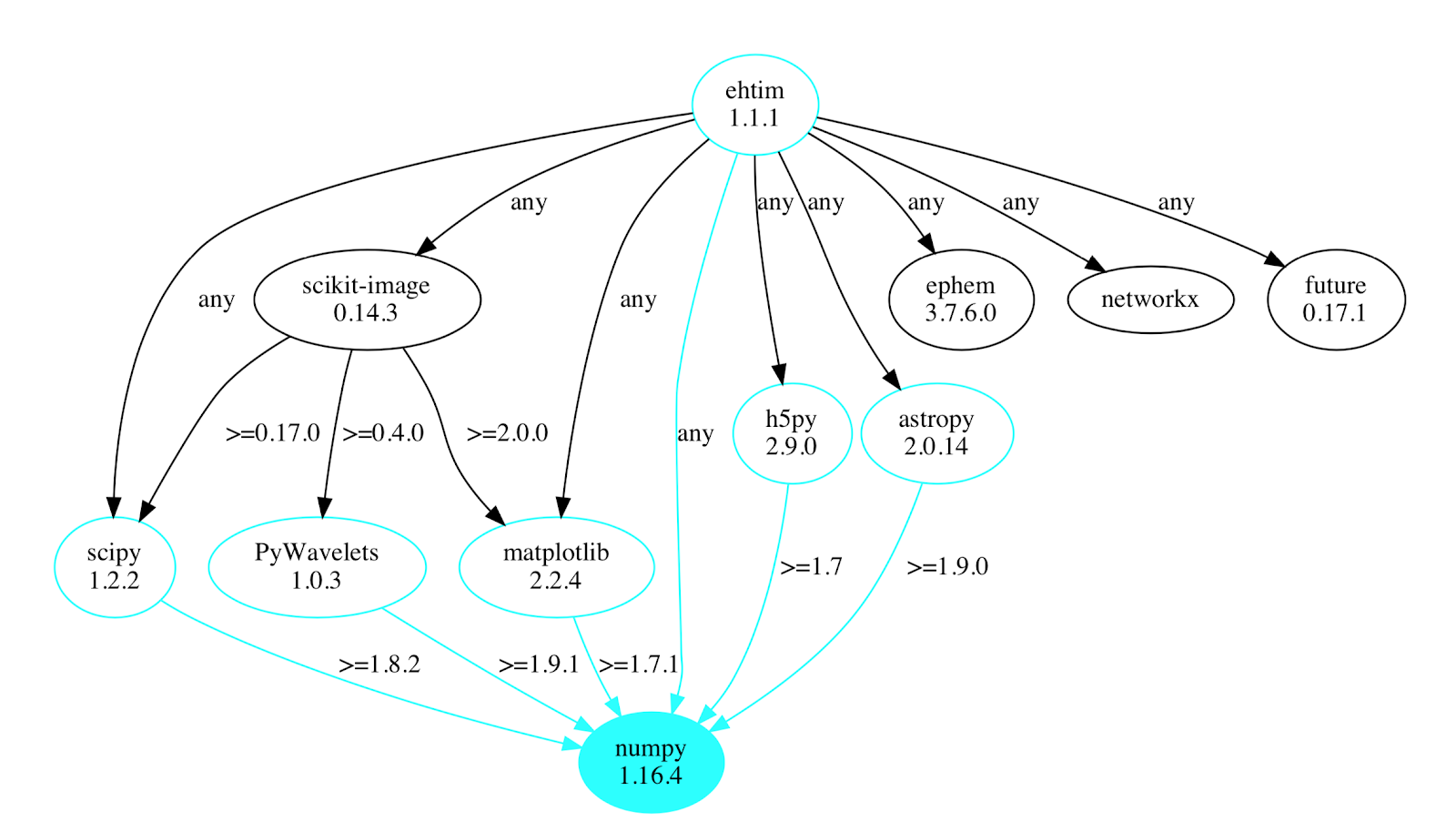

For example, the eht-imaging Python package provides tools for

simulating and performing image reconstruction on VLBI data.

NumPy is at the core of array data processing used

in this package, as illustrated by the partial software

dependency chart below.

Software dependency chart of ehtim package highlighting NumPy

Besides NumPy, many other packages, such as SciPy and Pandas, are part of the data processing pipeline for imaging the black hole. The standard astronomical file formats and time/coordinate transformations were handled by Astropy, while Matplotlib was used in visualizing data throughout the analysis pipeline, including the generation of the final image of the black hole.

Summary

The efficient and adaptable n-dimensional array that is NumPy’s central feature enabled researchers to manipulate large numerical datasets, providing a foundation for the first-ever image of a black hole. A landmark moment in science, it gives stunning visual evidence of Einstein’s theory. The achievement encompasses not only technological breakthroughs but also international collaboration among over 200 scientists and some of the world’s best radio observatories. Innovative algorithms and data processing techniques, improving upon existing astronomical models, helped unfold a mystery of the universe.

Key NumPy Capabilities utilized